I reach back in time to 2009 when the Hon Dr Nick Smith was the Minister for Climate Changes Issues and his introduction to the emissions trading scheme of the supermarket special the "two for one" deal.

I left the previous post on Industrial Allocation noting that in the 11 years from 2010 to 2020 there were 162 entities that were given, at no cost, 55 million emission units as they are deemed to be "emissions-intensive and trade-exposed".

In the same period the total actual emissions recorded in the Greenhouse Gas Inventory for all industries was 53 million tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent.

My data analysis is at this Git hub page Industrial Allocation.

Here is a barplot of the allocation (gifting, giving for free, donating) of the 55 million emission units to selected emitter industries.

Here is a barplot of the 53 million tonnes of actual emissions from the New Zealand industrial sector from the Greenhouse Gas Inventory.

Here is a line chart of the 53 million tonnes of actual emissions and the Industrial Allocation - the free allocation of the 55 million emission units.

So at first glance it appears that the amount of free emission units allocated cancel out the actual industry emissions. This suggests that in a net sense the industry sector emissions are not priced at all under the emissions trading scheme They are more than 'offset' by the allocation of free units. So it's the same net result as if the industry sector was completely exempted from the emissions trading scheme requirements to surrender emission units equal to their emissions.

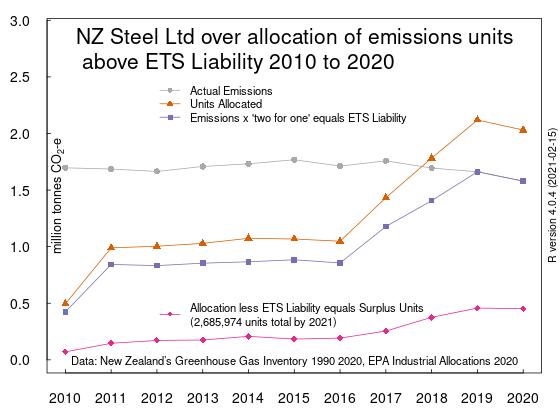

However I am missing a step in my analysis. In my detailed examples for New Zealand Steel and New Zealand Aluminium Smelters, I estimated the actual liability to surrender units by multiplying the Greenhouse Gas Inventory steel and aluminium emissions by a variable representing the "two for one" discount introduced in 2009 by the Hon Dr Nick Smith when he was the Minister for Climate Changes Issues.

On 1 September 2009 with Dr Smith's approval "Emissions trading bulletin No 11: Summary of the proposed changes to the NZ ETS" was published. It stated that the emissions trading scheme would be amended by adding a transition phase lasting to 31 December 2012 which would feature a "progressive obligation".

A transition phase will operate until December 2012. The transition phase will be implemented through....a progressive obligation requiring SEIP and LFF participants to surrender only one unit for every two tonnes of CO2-e emitted

The 'progressive obligation' was effectively a 50% discount on the 'surrender obligation', the quantity of emissions units that emitters had to surrender. Each firms industrial allocation of emission units would in consequence also be halved as well.

Then in 2012, Minister for Climate Change Issues Tim Groser introduced the Climate Change Response (Emissions Trading and Other Matters) Amendment Bill. This bill extended the life of the "two for one" 'progressive obligation' indefinitely.

Finally, in 2016, Minister for Climate Change Issues Paula Bennett introduced a bill to "phase out" the 'progressive obligation' over three years from 2017 to 2019 by increments from the original "two for one" - 2 units per tonne to 1.5 to 1.2 to 1 unit per tonne of emissions. See the "EPA document ETS Surrender Obligations One for two phase out factsheet"

So I need to include a discount variable that is applied to the free emission units allocated to result in the "emissions footprint" of the allocation of units. The discount variable is 0.25 for 2010 (half obligation for half a year),then 0.5 from 2011 to 2016, 0.67 in 2017 ,0.83 in 2018 and finally one for one for 2019 and 2020.

This allows me to estimate of the carbon footprint or emissions footprint of all the units given under Industrial Allocation. As in this chart.

I can then add the 'emissions footprint' values or the emissions allowed by the free Industrial Allocation units to the chart of allocated emission units and actual industry emissions.

The chart shows a huge gap between the emissions footprint and the allocated units until 2017 when the two lines start to converge.

Then in 2019, the emissions foot print is the same as the units allocated as finally, under the emissions trading scheme, one emission unit does in fact equate to one tonne of emissions.

The total of the Industrial Allocation 'emissions footprint' over 2010 to 2020 is 89 million tonnes. Meaning that those 89 million tonnes have been "de-priced" by the emissions trading scheme.

Just a reminder. What is an emission unit? It's a right to emit greenhouse gases to the atmosphere.

Owning an emission unit is the same as permission to emit a quantity of greenhouse gases whether from smelting or just from burning coal oil or gas.

Being allocated a unit is the same as being told "go for it - you can just burn coal or oil or gas without penalty until a tonne of carbon dioxide is in the atmosphere".

It's the opposite of a price on carbon. It's a permit or licence to burn carbon.

The emissions footprint of Industrial Allocation, from 2010 to 2020, at 89 million tonnes, is twice as much as the actual emissions of the whole industry sector for the same period.

How can that possibly be the case? It is because of the energy allocation factor.

Industrial Allocation "de-prices" and removes the emissions price signal from some energy sector emissions in addition to the direct industry process emissions.

In a net sense Industrial Allocation is worse as a policy to reduce industry emissions than a complete exemption of industry from the emissions trading scheme. In a scenario of 100% exemption, at least all energy sector carbon emissions would in theory be priced.

Hence my headline conclusion Industrial allocation exempts from pricing twice as many tonnes of emissions than the actual total emissions for the industry sector.